The Complete Guide to Shodo: A Japanese Tradition That Calms the Mind Through Brush and Ink

Shodo (Japanese calligraphy) is one of Japan’s traditional cultural arts.

Writing characters may seem simple at first, but the time you spend holding a brush, surrounded by the scent of ink, and facing each stroke one by one naturally calms the mind and becomes a moment to connect with yourself. In the process of aiming for beautiful characters, you can learn important things such as focus, etiquette, and an attitude of approaching things with care.

In this article, we’ll introduce shodo in detail—its history, tools, and basic posture—while also sharing what an actual calligraphy experience is like.

Introduction: What Is Shodo?

“Shodo” is one of Japan’s traditional cultural arts, where you write characters using a brush and ink.

Shodo has goals beyond simply writing “beautiful characters,” such as expressing yourself and understanding words more deeply. In Japan, there is an old saying: “Sho wa hito nari.” It means “handwriting is a mirror of the self,” and people believe that your character, what’s in your heart, and even your education can be felt through your writing.

Shodo is simply writing characters, yet it is a Japanese tradition that allows you to calm your mind, face yourself, and learn important things as you write neat, beautiful characters.

Today, with more communication happening through typing on computers and smartphones and sending messages to others, opportunities to write on paper have sharply decreased. But when you write by hand, warmth and feelings come through in the characters. Precisely because modern society is filled with convenience, shodo is something worth rediscovering.

The History of Shodo

The “kanji” expressed through shodo originally emerged in China around 3,500 years ago. At that time, there was no paper. Characters were carved into turtle shells and the bones of animals such as cattle and horses. These are the ancestors of kanji, known as “oracle bone script.” Back then, they looked more like pictographs than the characters we know today. Over time, oracle bone script moved from shells and bones to being carved into bronze vessels and stone. Around 2,500 years ago, the pictographs gradually became more like written characters. As more and more forms appeared, China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, unified the writing system around 2,300 years ago. The script established then was “Small Seal Script (xiaozhuan).” From there came “Clerical Script (lishu),” which developed as a simplified form of seal script, as well as “Cursive Script (caoshu)” and “Semi-cursive Script (xingshu),” which were created to write more quickly. Eventually, “Regular Script (kaishu)” was born—the style used in Japan today, where each stroke is written clearly with stops, hooks, and sweeps.

There are various theories about when shodo began, but it is said to have been around 2,000 years ago. Characters that had been carved into stone and other materials began to be written with a brush. Later, people started to regard writing as something beautiful, which is considered the beginning of shodo.

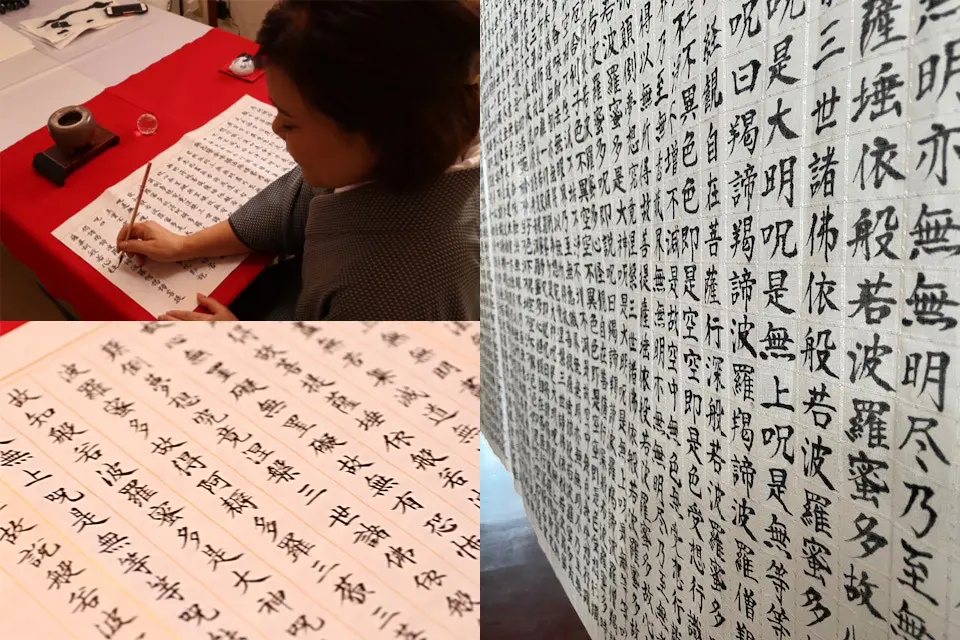

Shodo came to Japan along with the introduction of Buddhism, around the 6th to 7th centuries, from the Asuka period to the Nara period. In Japan, it began with copying Buddhist sutras, known as shakyo. Along with shodo came the making of brushes and ink, as well as papermaking. Writing with a brush and ink was an important form of education for samurai and aristocrats at the time. In the Heian period, when aristocratic culture flourished, nobles exchanged feelings by writing letters and composing waka poems. During this time, hiragana—based on kanji—was born.

Shodo and Japanese People

Shodo is deeply rooted in everyday life in Japan. Training to write characters with a brush and ink is learned in elementary school through Japanese language classes called “shuji” or “shosha.” It was introduced into elementary Japanese education in 1971 and became a required subject. That said, textbooks for “Japanese” and “shuji” are separate, and their learning goals are different. “Shuji” is practice in writing characters beautifully with a brush, focusing on techniques such as beauty, balance, and brush pressure. “Shosha,” on the other hand, teaches how to write characters accurately. The goal is to learn brush handling and write characters beautifully and correctly. Writing beautifully and correctly is necessary in daily life, such as when writing letters, which is why it is taught in compulsory education.

In high school, there is also a “shodo” class as an elective in the arts. It goes beyond “shuji” and “shosha,” which focus on brush technique and accuracy, and instead pursues the beauty and artistry of characters. Students consider the meaning and origins of characters and express them through ink tones and brush movement. So in Japan, once students reach high school, it is common to choose an arts elective—such as art, music, or shodo—rather than learning it as part of Japanese language class.

In this way, Japanese people have opportunities from childhood to experience shodo, a traditional cultural art of writing characters with a brush and ink. In many other countries, it’s rare for school education to include a curriculum for traditional culture, so visitors from overseas are often surprised. By the way, many elementary schools in Japan don’t have uniforms, but on days when there is shuji class, it was a memorable sight that most students would wear dark-colored clothes like black—even though there’s no dress code. That’s because when you’re not used to handling a brush, it’s easy to get ink on your sleeves.

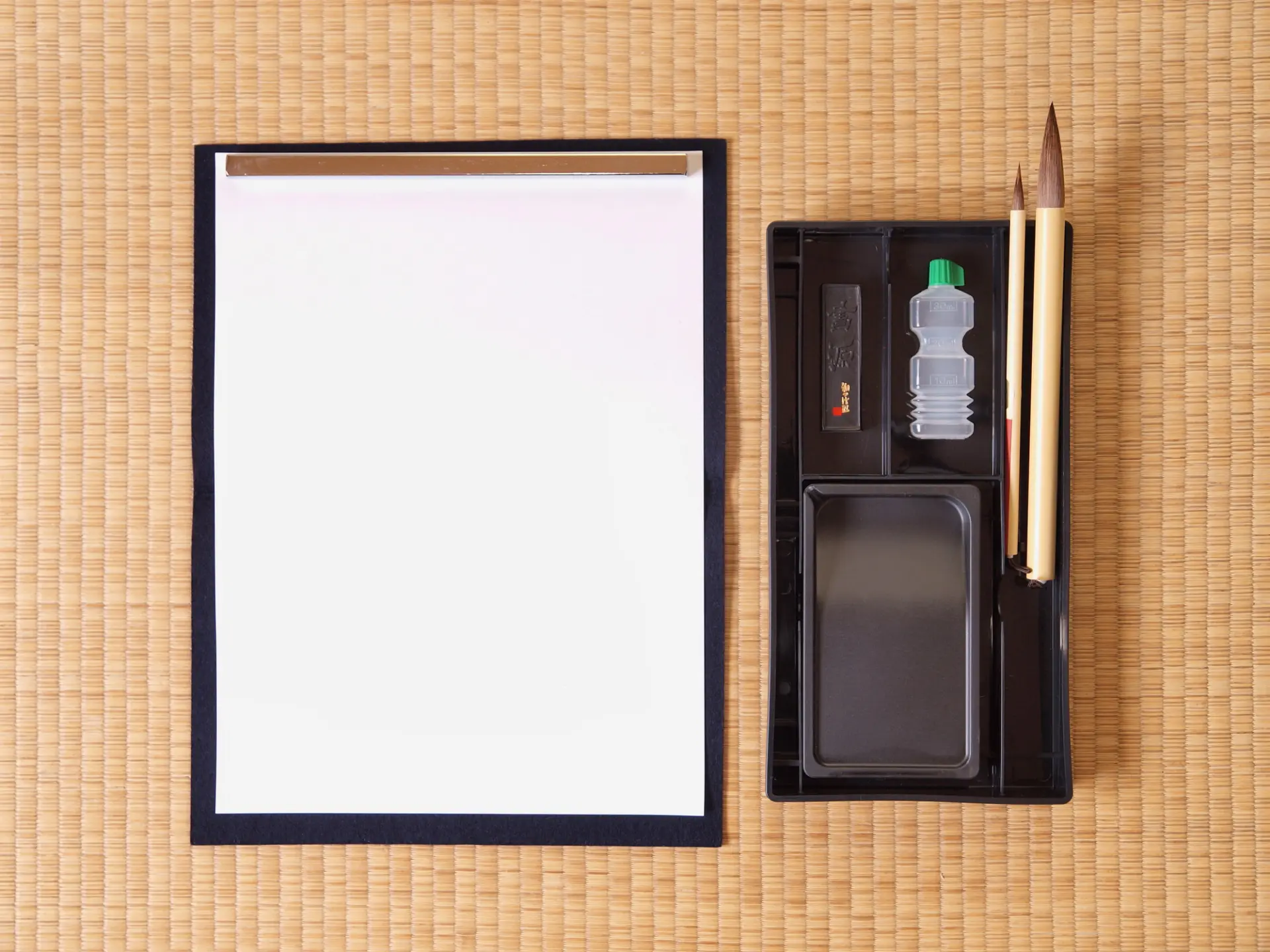

Shodo Tools (The Four Treasures of the Study)

The basic tools needed to begin “sho” are called the “Four Treasures of the Study” and refer to four items: brush, paper, inkstone, and ink.

“Study” means a scholar’s room, and the phrase “Four Treasures of the Study” has long been valued in China by those who practice calligraphy. In addition to the four tools—brush, paper, ink, and inkstone—paperweights and underlays are also essential for shodo.

In Japan, these tools are sold together as a calligraphy set.

1. Brush

There are many kinds of brushes, because you change the brush depending on the characters you want to write.

Brushes are classified by factors such as “tip firmness and material,” “tip length,” and “handle thickness.”

・Tip firmness and material

The part of the brush that holds ink and writes characters is called the “tip.” The main material for the tip is animal hair. Hair from sheep, horses, weasels, raccoon dogs, and others is used, and the firmness changes depending on the animal and which part of the body the hair comes from. With a brush made from firm hair, you can write powerful lines. A brush made from soft hair allows you to write characters with more movement. There are also mixed-hair brushes called “kengo,” which combine firm and soft hairs for a springy feel.

・Tip length

Tip length is divided into three types: long tips (“choho”), short tips (“tanpo”), and medium tips (“chuho”) in between.

With a long tip, you can write characters with movement and rich variation. With a short tip, you can write solid, steady characters. The characteristics of what you can write differ depending on the tip length.

・Handle thickness

Handle thickness is expressed by a “go” number. Sizes range from No. 1 at 2.1 cm to No. 10 at 0.5 cm. No. 1 to No. 3 are classified as thick brushes (futofude), No. 4 to No. 6 as medium brushes (chuhitsu), and No. 7 to No. 10 as thin brushes (saihitsu).

For beginners, a good choice is a “kengo” brush that is neither too soft nor too hard, with a medium tip (“chuho”), and a No. 4 handle that’s easy to hold.

Brushes are very delicate and must be handled with care—so much so that caring for your brush is said to be one key to improving in shodo. After use, you must rinse it with water and thoroughly wash out the ink. Because brushes can be damaged, you should not scrub hard. The key is to wash gently using the pads of your fingers. Rinse many times until the water runs clear. Leaving it as-is after washing can also damage the brush. After fully washing out the ink, let it air-dry naturally with the tip facing down. Make sure it is completely dry before using it again; otherwise, it can cause shedding or mold. The way tools are treated carefully and used for many years also reflects the Japanese spirit.

2. Paper

For shodo, you use Japanese washi paper made to let ink bleed easily. There are hand-made washi and machine-made washi, and paper characteristics vary depending on factors such as the production area and raw materials. For practice, machine-made paper that doesn’t bleed too much is often used. Paper can be easily damaged if stored in hot, humid places, so it’s best to keep it out of sunlight.

3. Ink

There are two types of ink: solid ink (ink sticks) and liquid ink.

To use solid ink, you add water little by little to an inkstone and grind it by hand to make ink. Liquid ink, on the other hand, doesn’t need to be ground and can be used immediately. Because it’s easier to handle, liquid ink is often used in school classes. Solid and liquid ink also differ slightly when you write. Since solid ink is ground on an inkstone, the ink particles differ and the characters gain a sense of depth. Liquid ink has uniform particles, so the tone is consistent and it’s easier to write clean characters. It’s beginner-friendly. Liquid ink is convenient and easy to use, but solid ink also has its own appeal. Solid ink is made by kneading soot with nikawa (a natural adhesive), adding fragrance, pressing it into a wooden mold, and drying it. When you grind an ink stick, the pleasant scent of ink rises and calms the mind. It’s also an important time to settle your spirit before facing your own writing.

4. Inkstone

The shallow area at the front of the inkstone is called “land,” and the deeper area in the back is called “sea.” You make ink by adding a few drops of water to the land area and grinding, then adding a few more drops and grinding again, repeating the process. The key is to grind gently in a circular motion without applying too much force. If you press too hard, the particles become coarse and you won’t get good ink.

It’s also not good to add too much water at once. The surface of an inkstone is rough and has countless fine stone grains standing up. That’s why grinding creates ink with particles of various sizes. After using an inkstone, proper care is essential. Soak the inkstone in water and remove all ink from the surface, then rinse using a soft cloth. If ink residue remains caught in the stone grains, the ink’s color will become dull and you won’t be able to write well.

Shodo Basics

Shodo basics include correct posture and how to hold the brush.

1. Correct posture

Correct posture is a posture that doesn’t strain your neck or shoulders. Straighten your back and lift your chest. It’s easy to tense up, but try to relax your shoulders. It’s said to be good to leave about the space of one tennis ball under the armpit of your brush hand. The key is to keep your arm about one fist’s width off the desk. Keep your elbow and hand at the same height. This correct posture is essential as the first step to improving in shodo. If you can write in this posture, it reduces strain on your shoulders and neck, improves circulation, and is believed to increase concentration. When writing, you may focus so much that you forget to breathe, so remember your breathing as well. Above all, it’s important to keep your body relaxed and avoid putting force anywhere. If you do it many times, you’ll gradually get used to it.

2. How to hold the brush

Hold the brush slightly closer to the tip than the center. Holding it near the tip may feel more stable, but it can make the brush too fixed and harder to move freely in larger motions. There is the “tankō” grip, where you hold the brush with your thumb and index finger, and the “sōkō” grip, where you hold it with three fingers: thumb, index finger, and middle finger. The tankō grip is the same as holding a pencil. The sōkō grip is a stable way to hold the brush. The most important point is not to lay the brush down. The key is to keep it upright, straight toward the paper. It’s also important not to squeeze too tightly and to hold it with relaxed strength.

Shodo Experience

The Only Studio in Kyoto Where You Can Learn Directly from a Calligrapher

In Kyoto, there is a shodo studio where you can be taught directly by a calligrapher.

“Calligraphy Kyoto Chifumi Shodo Class,” located in Nakagyo Ward, Kyoto City.

This is the only place in Kyoto where you can learn from a calligrapher directly.

Your instructor is Chifumi Niimi, a calligrapher born and based in Kyoto.

With a mother who was also a calligrapher, shodo was close to Niimi from childhood, and he chose the path of calligraphy himself.

He has over 50 years of calligraphy experience and has been running a studio in Kyoto for over 35 years.

Beyond leading the class, Niimi has performed live calligraphy both across Japan and around the world.

He has also held calligraphy workshops in places such as Taiwan, India, Germany, Hawaii, and Spain. In 1989, Niimi studied calligraphy abroad at Fudan University in Shanghai and Peking University, where he learned English and Chinese. As a result, he is highly skilled in languages.

At the studio, he can provide direct instruction in English and Chinese without an interpreter, offering high-quality service with detailed follow-up. People from all over the world—including the U.S., Europe, France, Switzerland, the U.K., Belgium, and Taiwan—have visited the Kyoto studio to learn shodo from Niimi. Many return again, often bringing friends or family on repeat visits.

The studio can accommodate up to around 10 people. Because the experience is very popular, advance reservations are required. Reservations can be made via the website. The many brushes of all sizes displayed inside are truly impressive.

Facility Overview

- Name in Japanese

- カリグラフィー京都 知ふみ書道教室

- Address

- 199 Tawarayacho, Tomikoji Nijo-sagaru, Nakagyo-ku, Kyoto, Kyoto Prefecture (down Tomikoji St., just south of Nijo St., at the back of the alley in front of Doshin Children’s Center) Google Maps

- Event Days

- Monday-Sunday

- Hours

- 8am-9pm

- Website

- Website(English)

Try the Shikishi Artwork Course!

At Calligraphy Kyoto, the easiest way to try shodo is the Shikishi Artwork Course.

The experience fee for this course is 15,000 yen per person, and it takes 1 hour.

① Start with meditation

Once you arrive, you begin with meditation. Shodo shares something in common with Zen, so you first meditate to center yourself, then face the characters you will write.

① Tool explanation

Next is an explanation of the tools.

We learned that brushes are made from animal hair such as horse, goat, and weasel; that hanshi is a type of washi made from tree-bark fibers; and that ink comes in solid and liquid forms. With solid ink, you grind it on an inkstone while adding water. Since grinding solid ink takes time, we used liquid ink this time.

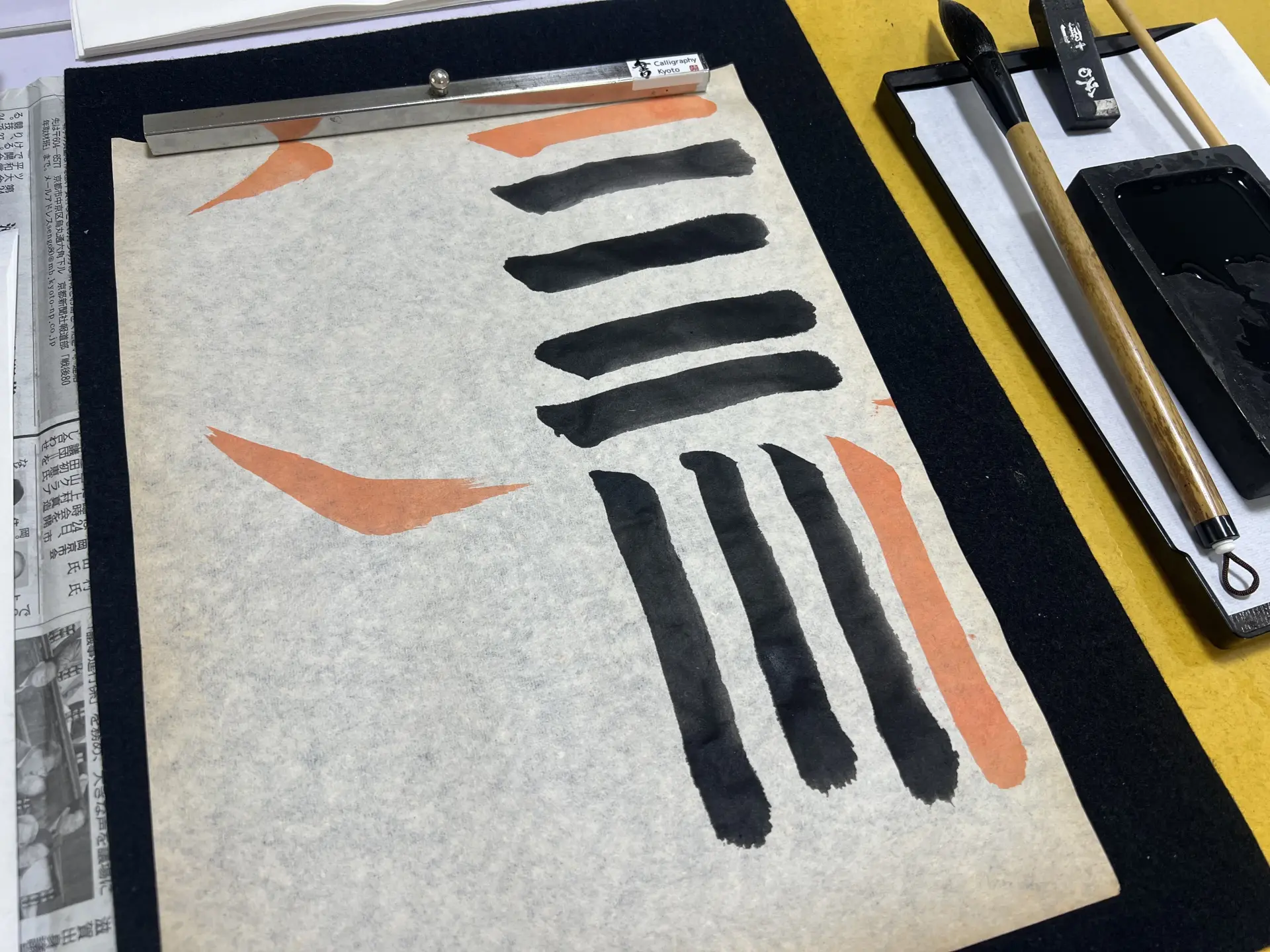

③ Practice “tome,” “hane,” and “harai”

We started by practicing the basics of “tome,” “hane,” and “harai,” which are elements that make up kanji.

Following the red “tome,” “hane,” and “harai” that Niimi wrote, we practiced using a thick brush. He taught us what to watch out for with each character, so we could quickly improve our habits and what needed fixing.

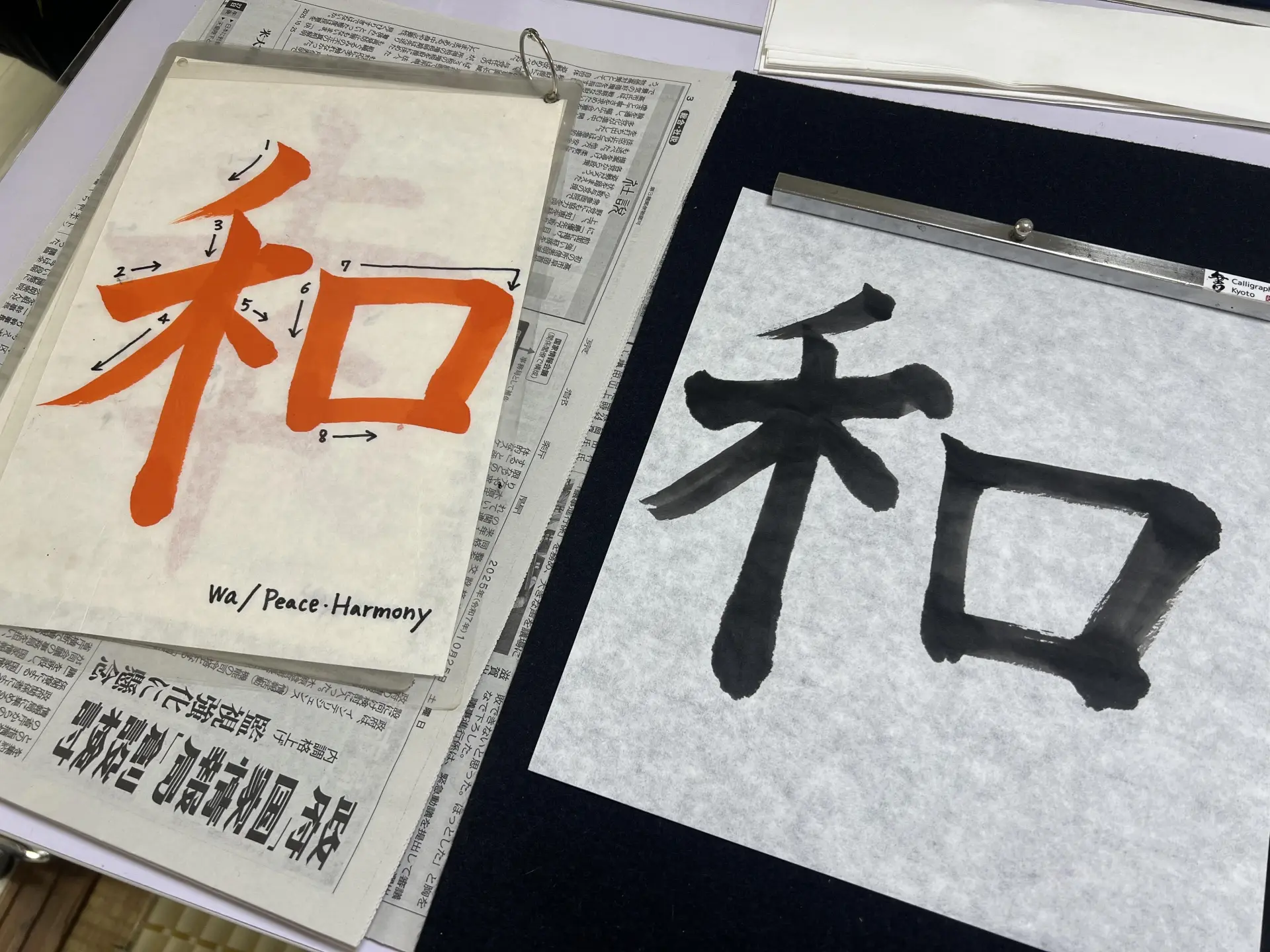

④ Choose your favorite character from the samples

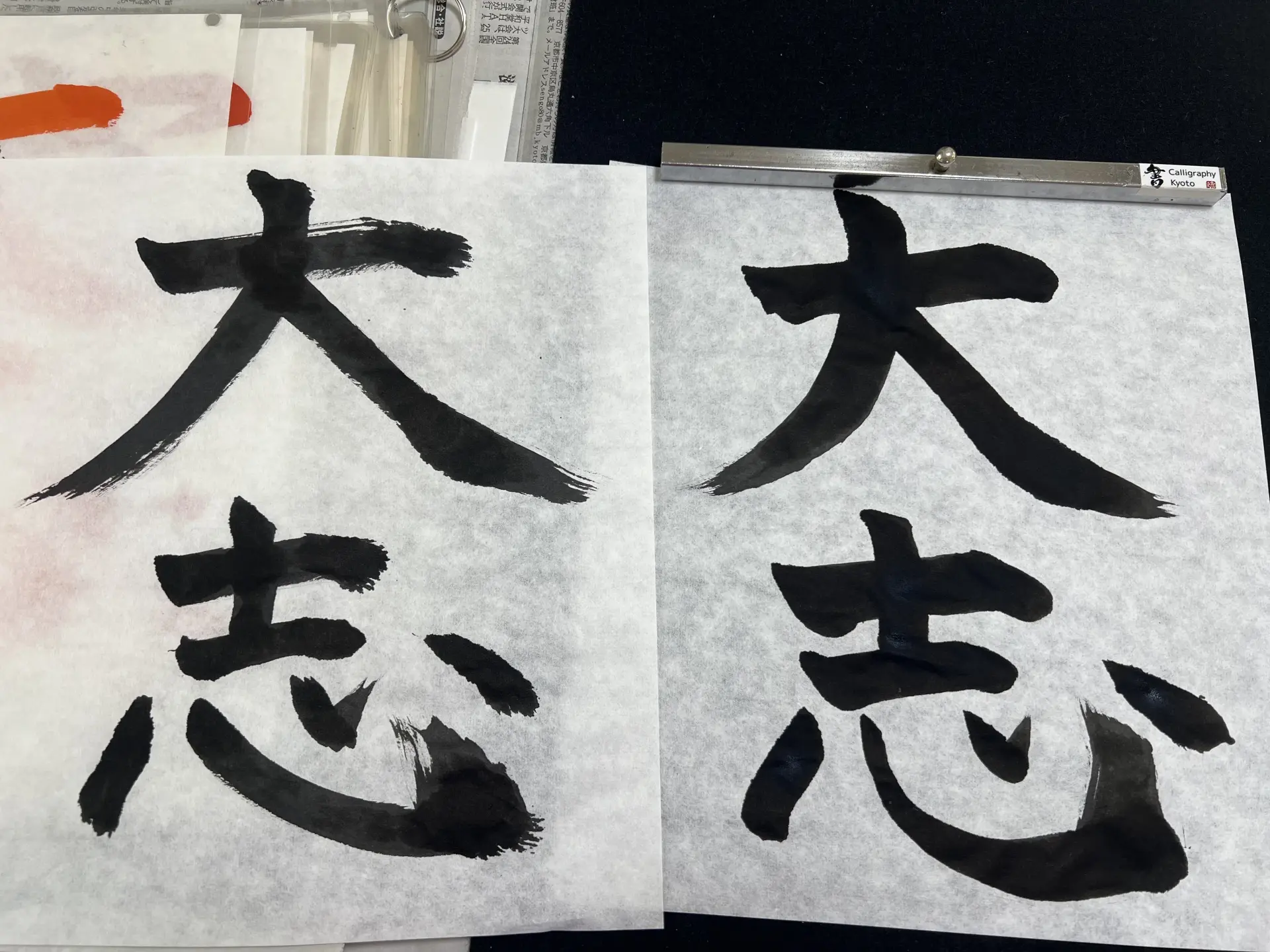

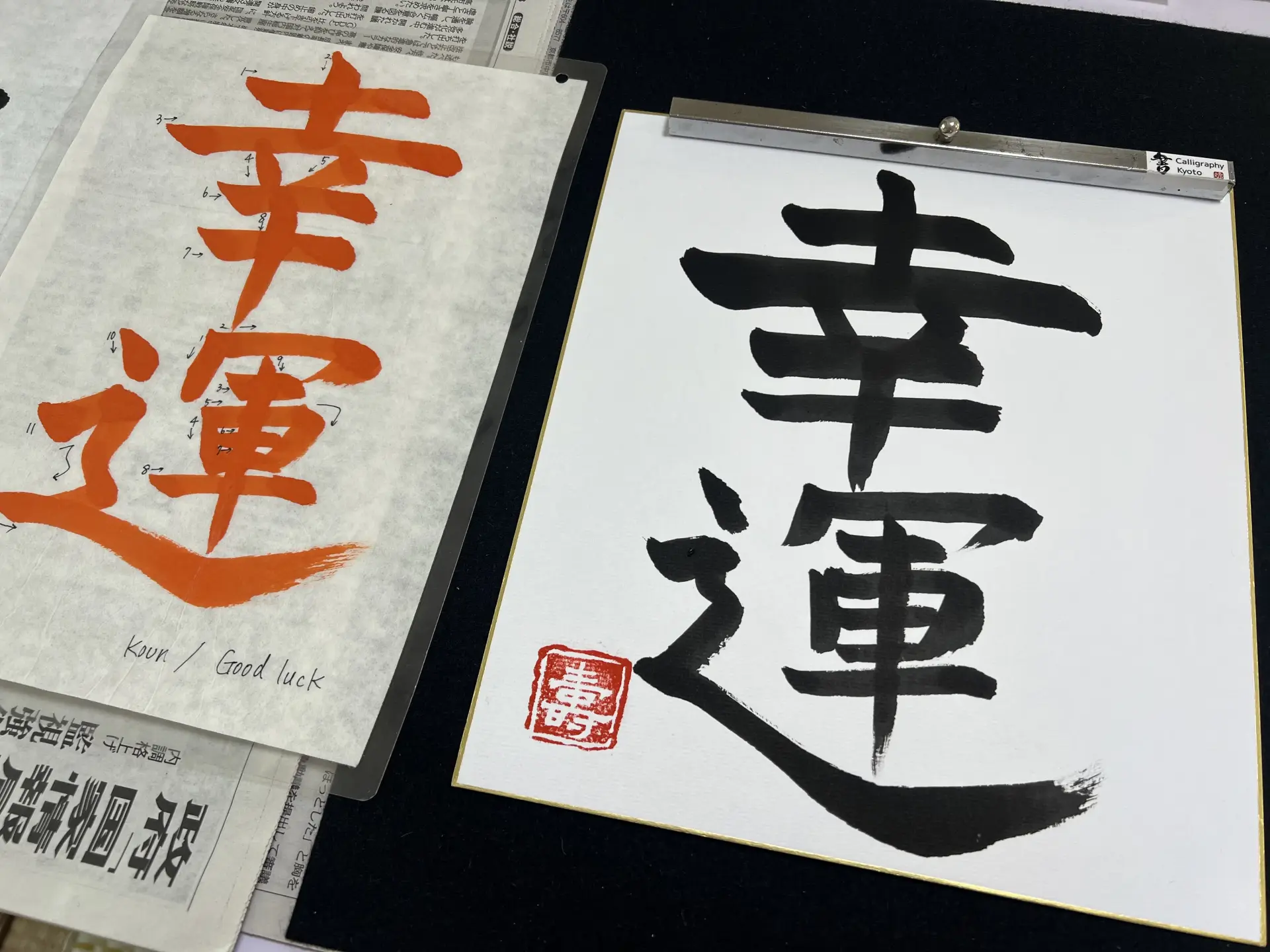

There are sample kanji written by Niimi, and you choose the one you want to try. Options range from single characters like “真” and “美,” to two-character words like “大志” and “幸運,” and even four-character idioms like “一期一会” and “日進月歩.”

A good recommendation is to start with a single character. Once you choose, Niimi teaches you not only the stroke order, but also the meaning of the kanji. This time, I chose “和.”

He even explained that “和” is read “wa” and means things like “peace” and “harmony.” Learning the meaning of the kanji changes the feeling you put into each stroke even more.

Now, we try writing it exactly like the sample—but before that, touch the hanshi and check the front and back. If it feels smooth, it’s the front; if it feels rough, it’s the back.

I tried writing it like the sample, but it felt a bit unbalanced. Niimi gave me direct advice on what to improve.

Also, when writing kanji, I naturally focused so much that I was holding my breath without noticing. Niimi reminded me each time to breathe properly and correct my posture while we practiced.

⑤ Keep writing and improve!

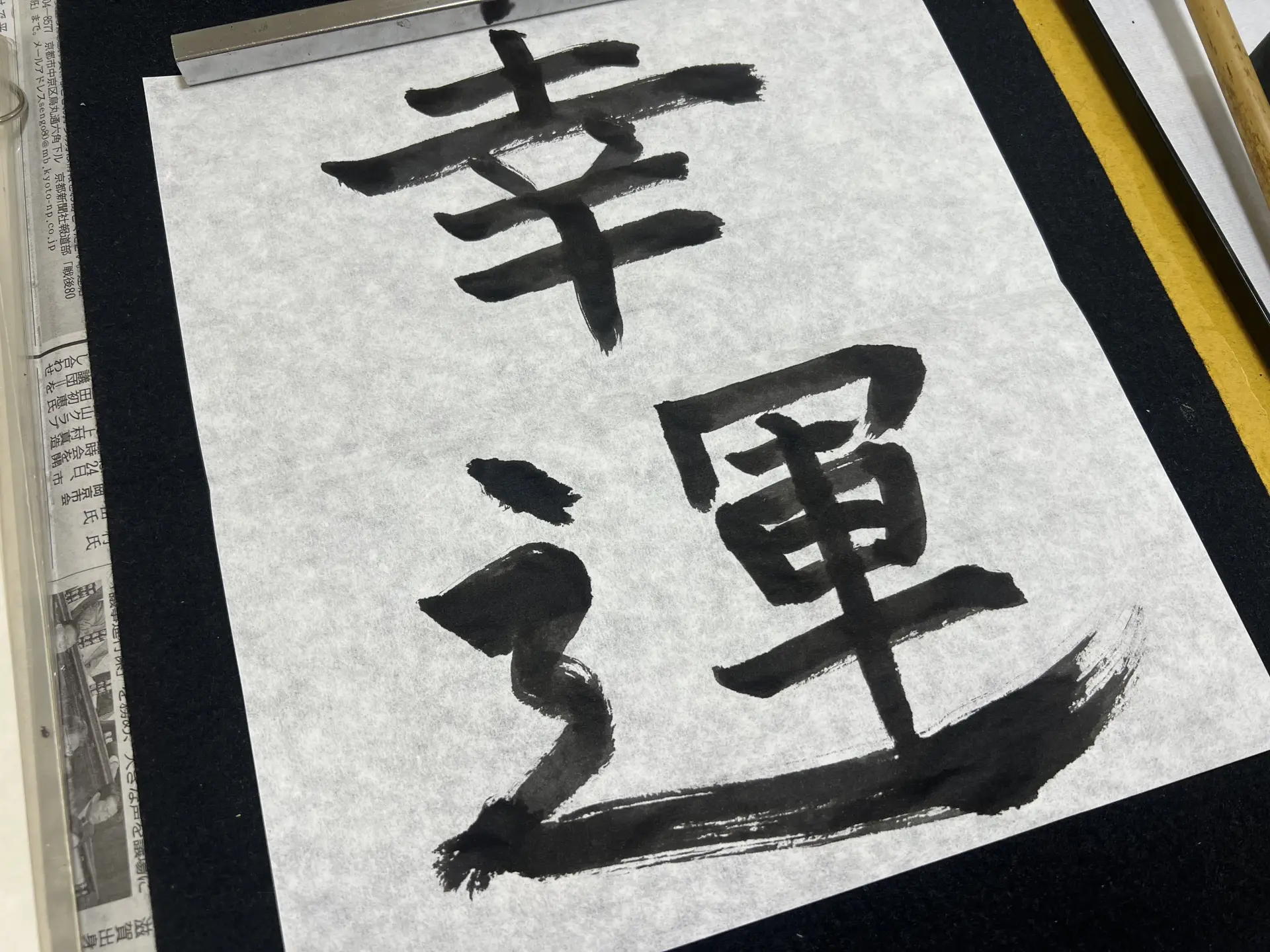

To get better, you need to keep practicing. After practicing single characters, try two-character and four-character words next.

Next, I challenged “幸運,” meaning “good luck,” like “GOOD LUCK” on this website, “GOOD LUCK TRIP”!

I could write “幸” with good balance, but I just couldn’t get the balance right for “運.”

Niimi taught me that the dot in the “shinnyo” radical should be written a little more to the right, and that the start of the “nyoro” stroke should be angled a bit more up to the right.

Also, the advice I received while writing the kanji for “大志” was memorable. There is a phrase like “Embrace your ambition,” but my writing had many dry, scratched parts, and I didn’t feel much of the dynamism that “大志” suggests. Niimi advised me that “there isn’t enough ink in the brush” and that “the writing speed is too fast.” When I tried again while paying attention to those two points…

There was almost no dryness, and I ended up with a bold “大志” that seemed to express “embracing ambition” through the characters themselves!

By practicing again and again based on Niimi’s advice, I could see myself getting closer to characters I felt satisfied with.

⑥ Final copy on shikishi

Once you’ve practiced enough, it’s time for the final copy. You can write your favorite kanji on a shikishi board. I chose “幸運,” which I struggled with in the “shinnyo” part. I soaked the brush with plenty of ink and wrote carefully, paying attention to what I’d learned—but also boldly, putting my feelings into each stroke.

It turned out better than practice… I think? I ended up with a piece I was happy with.

⑦ Add your signature

In shodo, once your work is finished, you add your name. This is called “rakusei kanshiki.” Using a thin brush, you learn how to write your name in katakana.

⑧ Frame it to finish

Place the finished shikishi into a calligraphy frame. It turned into a very cool piece!

Of course, you can take home both your shikishi and the hanshi sheets you practiced on. You can display it at home in the frame.

Since the hanshi is the same size as the calligraphy frame, you could also swap out the characters depending on your mood.

⑨ Lots of souvenirs

You take your artwork home in a tote bag designed by Niimi.

We also received a clear file and postcards.

Stepping away from the hustle and bustle of the city and spending time calmly facing each character felt very Zen-like. I hadn’t liked my handwriting much before. I often thought I wished I could write better, or write in a more mature style. But learning from Niimi helped me write with better balance, and I began to feel that my own handwriting might not be so bad—and I started to like the characters I write.

Other Experience Options

Calligraphy Kyoto also offers other well-rounded experience courses.

・Large Hanging Scroll Artwork Experience (6 hours / 70,000 yen per person)

In this course, you create a large hanging scroll.

Before making the hanging scroll, you of course get a kanji lesson.

You do it using a large brush for creating the hanging scroll.

A key feature is that you can write powerful, large characters.

You can also make your own stamp used for rakusei kanshiki.

・Mini Hanging Scroll Artwork Experience (2 hours / 25,000 yen per person)

In this course, you create a small hanging scroll.

You’ll learn beautiful kanji and complete your artwork.

You can also make your own stamp for rakusei kanshiki, making this a rich, satisfying course.

・Kana Fan Making (2 hours / 20,000 yen per person)

The main focus is learning kana characters.

Kana are phonetic characters used in everyday life in Japan.

The characters look connected, creating a beautiful flow.

You write the “Iroha” poem or traditional poetry on a small scroll or a board.

You create it using a special small brush.

・Hanko & Sutra Copying Experience (2 hours / 20,000 yen per person)

There are also 2-hour courses, each 20,000 yen per person, where you can make a hanko stamp or copy sutras.

Summary

It has been Approx. 1,400 years since shodo came to Japan from China. Over that long span of time, Japanese people have written characters using brush and ink. Each character carries feelings for someone important.

I think handwriting reflects your mental state well. When you feel unstable, your characters can look shaky, and when you feel steady, you may write larger, stronger characters. One of the joys and attractions of shodo is trying to keep your mind calm and facing the characters you write, no matter what.

Today, communication by typing on computers and smartphones and sending messages instantly has become mainstream, and opportunities to write by hand on paper have greatly decreased. Still, handwritten characters naturally carry the writer’s warmth and feelings. Emotions and thoughtfulness that are hard to convey through a screen can reach the other person through your writing. Precisely because modern society is filled with convenience, shodo is something worth rediscovering.

When you visit Japan, be sure to try experiencing “shodo,” a traditional Japanese culture, while learning about the origins and meanings of characters.

Author

Freelance Announcer

Sayaka Motomura

Focused on sharing insights related to traditional culture, performing arts, and history.