The Ultimate Guide to Enjoying Noh, the Pinnacle of Japanese Traditional Performing Arts

Noh is a traditional Japanese musical drama made up of chanting (utai), musical accompaniment (hayashi), and dance (mai). It is a kind of musical theater and is often described as a "traditional Japanese musical".

Noh actors wearing masks dance and act out the story to the sound of flutes and drums. They do not show emotion directly through their facial expressions but instead express feelings through angles, movements, and codified gestures called kata.

Often the main characters are not humans but beings such as demons, restless spirits, and deities, and noh depicts life and death, joy and sorrow through a supernatural world. This article introduces the profound appeal of noh, whose minimal staging stimulates the imagination of the audience.

Introduction

Noh is a traditional Japanese performing art. Noh, which consists of chanting (utai), musical accompaniment (hayashi), and dance (mai), is a form of musical drama and is often referred to as a "traditional Japanese musical".

Utai takes on the roles of dialogue, song, and narration, while hayashi is the musical performance. Mai corresponds to the dance. Noh is created by the combination of all these elements. The performers are called nohgakushi, or noh actors. In most plays, they appear on stage wearing various masks known as noh masks. To the accompaniment of flutes and drums played by the hayashi musicians and the chanting of utai, masked characters dance and unfold the story.

Some people may think, "If the actors' faces are hidden behind masks, how can you tell what they are feeling?" but that is not a problem. One of the fascinating aspects of noh masks is that their expression seems to change with slight shifts in angle or movement. You can also read the characters' emotions from their acting.

In performing a story, noh actors use fixed patterns of movement known as kata. They assume a basic stance called kamae, and when they move on stage, they slide their feet in a gliding walk called hakobi. Actions such as crying, feeling ashamed, shooting an arrow, or falling asleep are not improvised by the performer but choreographed according to predetermined kata. Through these kata you can understand what the characters are feeling. The fact that acting follows these set kata is one of the characteristic features of noh as an art form.

Another major characteristic is that the main character is often not a human being.

Demons, ghosts, deities, and other beings from beyond this world frequently take center stage. That does not mean noh is horror or suspense. Through these otherworldly characters, noh expresses the joys, struggles, and sorrows of living and delivers them to us, the audience.

Unlike most modern theater, noh is performed against a backdrop called the kagami-ita, a large board on which an ancient pine tree is painted. The physical space is fixed, but through the chanting it can represent many different settings, such as a shrine, a mansion, or a mountain. By keeping props, movement, and facial expression to a minimum, noh places its trust in the imagination of the audience and entrusts the experience to us.

In this article, we present a thorough guide to enjoying noh that will stimulate your sensibilities.

What Is Noh

The History of Noh

The roots of noh go back to the early Nara period. It is thought to have begun with sangaku, a performing art that came to Japan from the continent along with court music and dance. Sangaku combined various types of performance such as acrobatics, magic tricks, mimicry, and instrumental music. It spread both as entertainment offered at temple and shrine festivals and as street performance among the common people. Over time it came to be known as sarugaku.

From the mid-Heian to the Kamakura period, troupes of sarugaku performers serving temples and shrines appeared and performed dances at religious events as offerings to the gods. Around the same time, in farming villages, dengaku became popular: music and performance added to field rituals in which people played flutes and other instruments to cheer on rice planting. Dengaku was a performing art to pray for and celebrate a good harvest of the five grains. These two performing arts came to be called "sarugaku no noh" and "dengaku no noh" and developed separately in rivalry with each other. Eventually, however, dengaku no noh disappeared, and only sarugaku no noh survived.

Within sarugaku there were multiple groups called za, which were essentially theater troupes. Among them, in a troupe based in Yamato Province (present-day Nara Prefecture) during the Muromachi period, a performer named Zeami was particularly active. Zeami is an extremely important figure in the history of noh as a Japanese performing art. He was richly gifted and flourished not only as a noh actor together with his father Kanami but also as a kind of producer, playwright, and director. The era was the Muromachi period, during the time of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the third shogun who built the glittering Golden Pavilion, Kinkaku-ji. Zeami and Kanami won Yoshimitsu's favor and received his patronage.

With this backing, Kanami and Zeami incorporated the best elements of other popular performing arts of the time into noh and chose subject matter that appealed to their samurai and aristocratic patrons. They adapted hit works such as "The Tale of Genji" and "The Tales of Ise" into noh plays and in doing so established noh as a distinct performing art.

From the Azuchi-Momoyama period through the Edo period, the range of noh masks now in use took shape, and the costumes became more and more elaborate. Noh stages were built in Edo Castle and in the mansions of feudal lords, and many samurai studied noh.

Because noh actors served the shogunate and feudal lords, their status and position were stable, which allowed them to focus their efforts on acting and direction and helped noh to flourish.

Since Zeami established noh, it has been carefully passed down to the present day for more than 650 years.

Because its history is so long and unique in the world, noh was inscribed in 2001 on UNESCO's list of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

It continues to be performed today as a performing art that represents Japan.

Differences between Noh, Kyogen, and Kabuki

People often say they do not understand the differences between noh, kyogen, and kabuki. Noh and kyogen both have their roots in the same art of sarugaku. Put simply, noh is a musical drama, while kyogen is a dialogue-based drama. Kyogen is characterized by its quick tempo and focus on lively conversation.

The word kyogen originally meant "nonsense" or "idle talk" and was a common noun. Most kyogen plays are comedies that draw on the everyday lives of common people. They portray the foolish, ridiculous, and lovable sides of human nature with a satirical touch. In terms of acting and staging, noh and kyogen share some similarities, and together they are known as nohgaku (noh theater).

| - | Noh | Kyogen |

|---|---|---|

| Content | Focuses on legends, myths, and the spiritual world. | Focuses on everyday life and the lives of common people. |

| Expression | Expressed through chanting and dance and makes extensive use of masks. | Centered on spoken dialogue and rarely uses masks. |

| Atmosphere | Has a quiet, solemn, spiritual atmosphere. | Is bright, humorous, and full of human warmth. |

| Purpose | Seeks enlightenment and a mysterious beauty. | Aims to provoke laughter and offer satire. |

Kabuki, which was born in the Edo period, developed under the influence of both noh and kyogen.

Kabuki appeared about 300 years after noh and kyogen came into being. Noh theater and kabuki have similar types of musical accompaniment and similar stage structures. Many noh and kyogen plays have been adapted into kabuki. For example, the popular kabuki play "Kanjincho" is based on the noh play "Ataka", and the kyogen play "Boshibari" is staged in kabuki under the same title, written in a different way. Other kabuki plays such as "Funabenkei" and "Tsuchigumo" also have their origins in noh. Even when they share the same subject matter, the overall impression of the works can be very different, so it is fun to compare noh, kyogen, and kabuki.

Characters Who Appear in Noh

The characters on stage in noh vary by play, but there are some types that appear frequently. Here are some of the representative ones.

Deities

Male deities, female deities, and elderly deities appear, although most are male deities. These dignified gods radiate a solemn presence and perform dances of blessing.

Tengu

Tengu, who can display superhuman powers when necessary, usually look like yamabushi, ascetic monks who practice in the mountains. They wear a wig called a kashira and the small black headpiece known as a tokin that is characteristic of yamabushi. They also carry a feather fan.

Old men

Although they appear as old men, they are sometimes actually deities or spirits. In many plays their true identity is revealed in the latter half.

Generals and warriors

The ghosts of warriors from the Heike and Genji clans often appear. The way their costumes are worn suggests armor, and they may carry swords.

Celestial beings

Celestial beings appear in plays such as "Hagoromo". They are inhabitants of the heavenly realm. They wear an ornamental headdress called a tenkan, a symbol of high status, and dance in gorgeous costumes.

Demons

A typical demon is the transformed form of Rokujo no Miyasudokoro, who appears in the play "Aoi no Ue". Originally human, she is driven by jealousy, suffering, and anguish to take on a demonic form. Other plays feature demons whose bodies and minds are demonic from the start.

Monks

Many plays begin when a traveling monk encounters some strange occurrence. In many cases, the audience experiences the story from the monk's point of view. In the latter half of such plays, the monk often offers prayers and helps vengeful spirits find peace.

The Meaning of Noh Masks

Masks used in noh are called omote, or "faces," and they express the personality and character of the role. It is said that there are about 240 noh plays, and around 60 different basic noh masks are needed to perform them all. These basic forms are thought to have been completed between the Muromachi period and the early Edo period, and if you include special masks, there are now more than 200 types.

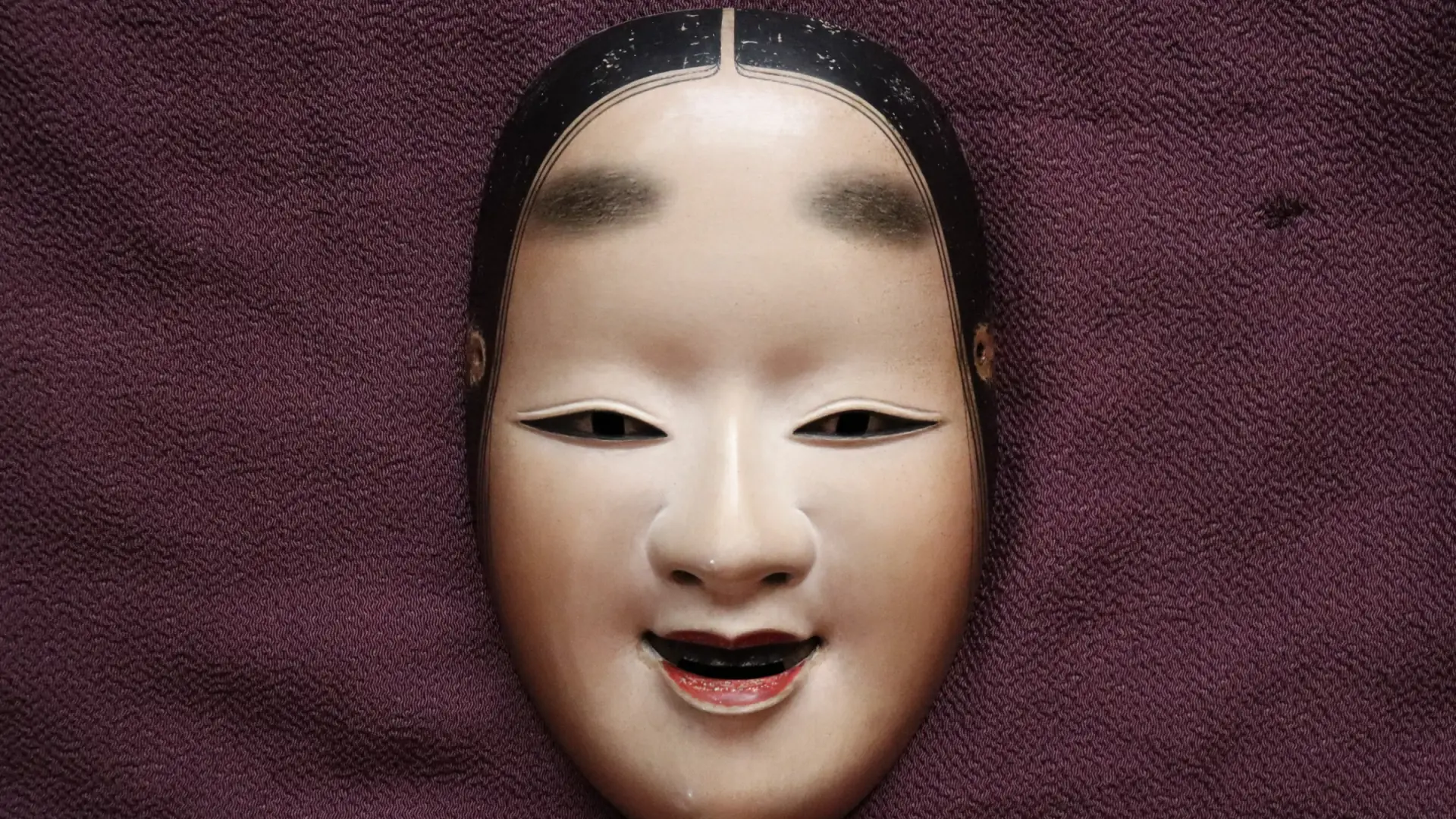

Masks that are used only for a single specific role are rare; as a rule, the same mask is used for multiple roles. If you look closely, you will notice that the eyes and eyebrows of a mask are deliberately carved slightly asymmetrically. By changing the angle just a little, the expression can look like a smile or can appear sorrowful. An upward tilt, called teru, makes the expression look brighter, while a downward tilt, called kumoru, makes it look darker. Here are a few representative masks.

Wakaonna (young woman mask)

This is the mask of a beautiful young woman and is used in a wide variety of plays.

Hannya

Although it looks like a demon, this is actually the mask of a woman. Driven mad by jealousy, she has taken on a demonic visage. Her eyes are full of sadness, while her mouth shows rage, and you can clearly see her wild, unkempt hair.

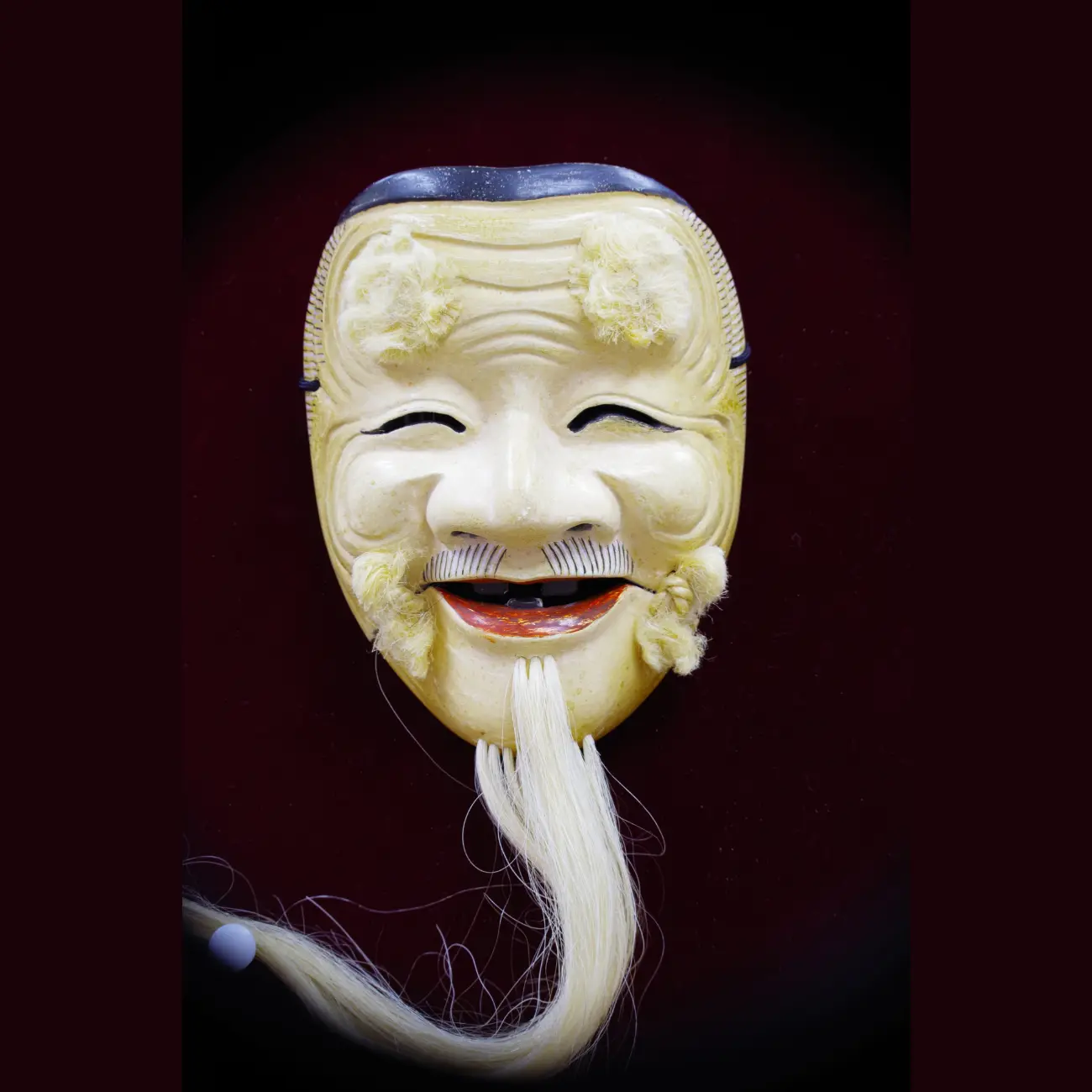

Okina

This mask is worn by the shite performer when playing Okina. When the face is white it is called Hakushikijo. The chin part is cut separately and tied on with strings, a feature not found in other noh masks.

The Noh Stage

Now let us look in detail at the noh stage.

1. Honbutai (main stage)

The honbutai is the central part of the noh stage. It is a square with each side measuring about 5.4 meters. Thick cypress floorboards are laid lengthwise toward the front of the stage. To make it easy for performers to walk, stamp their feet, and jump, no nails are used. The space under the floor is hollow so that sound will resonate. The stage is built with a slight tilt so that the front edge is lower, making it easier for the audience to see.

2. Kagami-ita (back wall with painted pine tree)

The kagami-ita is the wooden wall at the back of the stage.

It is always painted with an old pine tree, an auspicious plant.

Because pine trees do not wither and remain green forever, they symbolize eternal prosperity.

It is believed that deities descend into pine trees.

3. Atoza (rear stage)

The atoza is the area behind the main stage. The stage attendants and hayashikata sit here. On the main stage the floorboards run lengthwise, but on the atoza they run crosswise, so this area is also called the "cross boards". When performers are in the atoza to change costume in the middle of a play, they can be seen from the audience, but they are treated as if they are invisible.

4. Jiutaiza (chorus seating)

The jiutaiza is the area to the side of the main stage where the chorus sits. Typically, eight chorus members sit there in two rows of four. When the noh stage is used for kyogen, this area is not used.

5. Shirasu (white gravel area)

The shirasu is the space filled with white stones between the noh stage and the audience. It is a remnant of the time when noh stages were outdoors and is said to have served as a reflector, bouncing sunlight onto the masks and costumes to illuminate them.

6. Metsukebashira (sighting pillar)

When actors wear masks, their field of view narrows and it becomes hard to judge distance, so this pillar was used as a landmark to help them confirm direction and position, which is how it got its name. In addition to the metsukebashira, there are three other pillars on the noh stage, named in clockwise order from the metsukebashira: the shitebashira, near which the shite often begins performing; the fuebashira, near which the flute player sits; and the wakibashira, near which the waki usually sits.

7. Kizahashi (front steps)

The kizahashi is the short staircase attached to the center front of the main stage. Although it is not used today, during the Edo period officials climbed up these steps to give the signal to begin a noh performance or to present rewards. It remains on modern stages as a vestige of that time.

8. Kiridoguchi (side entrance)

The kiridoguchi is the sliding door at the back on stage right. The chorus and stage attendants enter and exit through here.

9. Hashigakari (bridgeway)

The hashigakari is the corridor-like space that extends diagonally back to the left from the main stage. It serves both as a passageway between the mirror room and the main stage and as a performance area. Its length is usually around 10 meters.

10. Agemaku (curtain)

The agemaku is the curtain that hangs between the mirror room, a sacred space where performers focus their minds and put on their masks, and the hashigakari.

It is striped vertically in five colors representing "wood, fire, earth, metal, and water." (In some cases it has three colors.) When performers enter or leave the stage, the curtain is raised and lowered. When performers wearing costumes, such as the shite or waki, pass through, the curtain is fully raised, which is called honmaku. When hayashikata pass through, only the side near the wall is slightly opened, which is called katamaku.

11. Bugyo-mado (magistrate's window)

The bugyo-mado is a window in the wall beside the agemaku, with a bamboo blind hanging inside. From the mirror room where this window is located, people can watch the progress of the performance and observe the audience. It is said that in the Edo period government officials (bugyo) peered out from here to keep watch, which is how it got its name. It is also called the arashi-mado or monomi-mado.

12. Matsu (Ichi-no-Matsu, Ni-no-Matsu, San-no-Matsu)

These are the three pine trees planted at equal intervals in the shirasu area along the hashigakari. The three trees are different in size, growing smaller the farther they are from the main stage. They serve as reference points for where to stand when performing on the hashigakari. Counting from the tree closest to the stage, they are called Ichi-no-Matsu (the first pine), Ni-no-Matsu (the second pine), and San-no-Matsu (the third pine).

13. Kininguchi (entrance for distinguished guests)

This was once used as the entrance and exit for people of high rank, but it is no longer used today.

14. Kensho (auditorium)

In noh, the audience seating area is called the kensho. Until the early Showa period, many kensho had tatami mats, and people watched while sitting formally on their knees. Today, most kensho have chairs. Different sections of the kensho have different names. The area facing the front of the main stage is called the shomen, the area viewing the main stage directly from the side is the wakishomen, and the area that fans out diagonally from the metsukebashira is the nakashomen.

People Who Perform Noh

Professional noh performers are called nohgakushi.

They are broadly divided into tachikata, who are responsible for chanting and acting, and hayashikata, who play the instruments. Tachikata in turn are divided into shite-kata, waki-kata, and kyogen-kata. Waki-kata, kyogen-kata, and hayashikata together are referred to as the sanyaku, or "three supporting roles".

Hayashikata are further divided into fue-kata (flute), kotsuzumi-kata (small shoulder drum), otsuzumi-kata (large hip drum), and taiko-kata (stick drum).

Because each role requires specialized skills, performers do not change their role or school once they have chosen one. In a typical noh performance, at least 16 people appear on stage, and in some cases more than 20 performers take part.

1. Shite-kata

Shite

The shite is the leading performer of the play. There is no noh play without a shite. The shite often plays non-human characters such as demons, deities, or ghosts. In such cases the shite wears a noh mask. The shite also serves as a kind of artistic director overseeing the production as a whole.

Shite-zure

The shite-zure is the supporting performer who plays the second most important role in the play. They often appear as the shite's companion or ally.

Kokata

Kokata are children's roles.

They appear, for example, as Umewakamaru in the play "Sumidagawa" or Ushiwakamaru in "Kurama Tengu".

Koken

Koken are stage attendants who ensure that the performance proceeds smoothly.

They usually sit toward the back of the stage, and there are often two or three of them. Before the performance, they dress the shite in costume. During the performance, they help when the shite changes costume on stage, when a costume becomes disordered, or when props are needed. Because they must keep the performance running without interruption, they have to understand the entire flow of the play, including the staging and the positions of all performers.

For this reason, koken are usually more senior performers or the shite's own teachers.

Jiutai

The jiutai performs the chanting that includes songs, dialogue, and narration.

Around eight jiutai typically sit to the right of the stage and chant together in unison.

2. Waki-kata

Waki

The waki often appears first, explaining the setting of the story and drawing the audience into the world of the play. The waki brings out and receives the shite's performance. While the shite often plays beings from beyond this world, the waki is usually a living adult man, such as a traveling monk, an imperial messenger, or a warrior. Because the waki represents a character in the real world, he does not wear a mask.

Wakizure

Wakizure usually play the companions or retainers of the waki.

3. Kyogen-kata

Ai

The ai character, played by a kyogen actor, usually appears between the first and second halves of the noh play. The ai explains stories related to the shite and serves as a bridge between the two halves.

4. Hayashikata

Hayashikata are the performers who play the instruments. They use the flute, kotsuzumi, otsuzumi, and taiko, each played by a specialist. Depending on the play, there may be no taiko. Their performance is one of the key elements that enhances the chanting and acting.

Let’s Visit a Noh Theater

In Okazaki in Sakyo-ku, Kyoto, many of the city's cultural and artistic institutions are gathered in one area. Here you will find Heian Jingu Shrine, the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, and Kyoto City Zoo, and nearby flow the Shirakawa River and the Lake Biwa Canal. In spring the cherry blossoms are beautiful, and in autumn the autumn leaves are stunning, making it a district where the streets themselves exude a refined atmosphere.

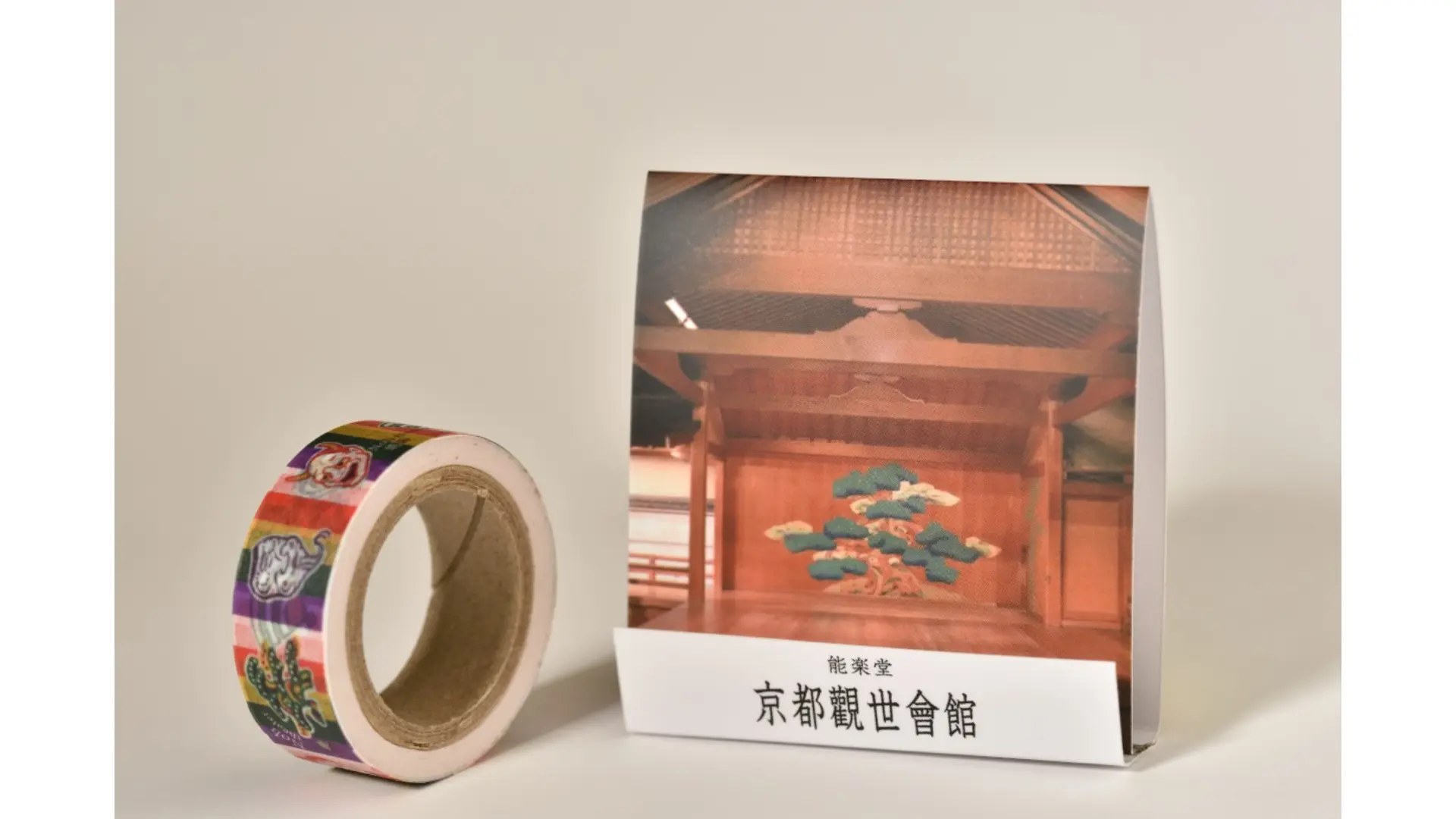

Located in this scenic area is Kyoto Kanze Noh Theater.

The noh stage at Kyoto Kanze Noh Theater is built entirely of cypress, and the pine tree on the kagami-ita was painted by Domoto Insho, a leading Kyoto nihonga (Japanese-style painting) artist, making it a work of great value.

There is no strict dress code when visiting a noh theater, and you do not need to wear kimono to enter. Because you will be seated for a long time, it is best to wear something comfortable. The auditorium can sometimes feel a little chilly, so it is a good idea to bring a jacket or some other layer that is easy to put on and take off.

The World of ENTER NOH

What Is ENTER NOH

At Kyoto Kanze Noh Theater there is a program for international visitors called ENTER NOH, which offers explanations of noh in English followed by a chance to watch an actual performance. In 2025 it was held four times. Because there are not many tourist attractions in Japan that can be enjoyed at night, this program was created as an evening activity for visitors, and the performances start at 8:00 pm.

*The information in this article is based on coverage conducted in October 2025.

Let’s Buy Tickets

Tickets can be purchased online.

There are four types of tickets: S seats with a backstage tour, regular S seats, A seats, and student tickets. S seats with the backstage tour cost 25,000 yen. S seats cost 12,000 yen. A seats cost 10,000 yen. Student tickets cost 3,500 yen.

Join ENTER NOH

For ENTER NOH, the ticket that includes the backstage tour is especially recommended. Those who purchase this ticket can go behind the scenes before the performance.

First, participants gather in the audience seating area, where staff explain what you are going to experience.

After that, you go backstage. Because this is a sacred space where outdoor shoes are not allowed, you must wear tabi socks or plain white socks.

White socks can be borrowed. From there, you move to the dressing rooms.

You are allowed to enter the kagami-no-ma, or mirror room, where noh actors put on their masks. Then the agemaku curtain is raised, and you walk from there along the hashigakari bridgeway and actually step onto the stage.

On stage, staff explain how wearing a noh mask limits the actors' field of vision. If you make a triangle with your hands and look through it, you will experience something very close to what the actors see from inside the mask.

Next you exit through the kiridoguchi, pass through the dressing rooms, and view the large stage props such as the frame of a boat that are used in performances, all while receiving explanations.

Climbing to the second floor, you find a display of costumes and noh masks lined up in rows. You can see magnificent costumes and historically important masks from close up.

Finally, you can watch a noh actor being dressed in full costume. You are allowed to take photos of the dressing process.

Once the dressing is finished, the actor also puts on a noh mask, and you can have a commemorative photo taken together with the fully costumed performer. This is very popular and is sure to become a once-in-a-lifetime memory. The backstage tour lasts about one hour and offers a very satisfying experience.

The Flow of the ENTER NOH Experience

From this point on, the program is the same for all ticket holders: you watch and enjoy an actual noh performance.

1. Explanation

First there is an explanation in English about noh, lasting about 20 minutes. A guide who is also a noh performer explains in detail what noh is and what kind of play will be performed.

2. Performance

The noh performance itself is performed in Japanese. To help you follow the story, you can borrow a device that provides English subtitles showing what is being said.

In 2025 the plays performed are "Aoi no Ue" and "Funabenkei". One of these two plays is performed on each performance date. Both are easy for beginners to understand, so you can relax and enjoy them.

3. Bonus Scene

After the performance, the final highlight scene of about three minutes is performed once again. During this second performance of the scene, you are allowed to take photos and videos. Because filming during the performance is normally not permitted, this is a very special service. Take plenty of photos and videos and bring your memories home with you.

Let’s Buy Souvenirs

If you visit Kyoto Kanze Noh Theater, be sure to pick up some souvenirs related to noh. One particularly impressive item is the "Kesho-no-Omote Cosmetic Pouch".

-

Kesho-no-Omote

-

Cosmetic Pouch

Shaped like a woman's noh mask, the pouch can hold makeup brushes, eyeliner, mascara, or items such as eye shadow and blush. It works perfectly as a cosmetic pouch and is also very convenient as a pencil case. You can even purchase this item through online shopping sites.

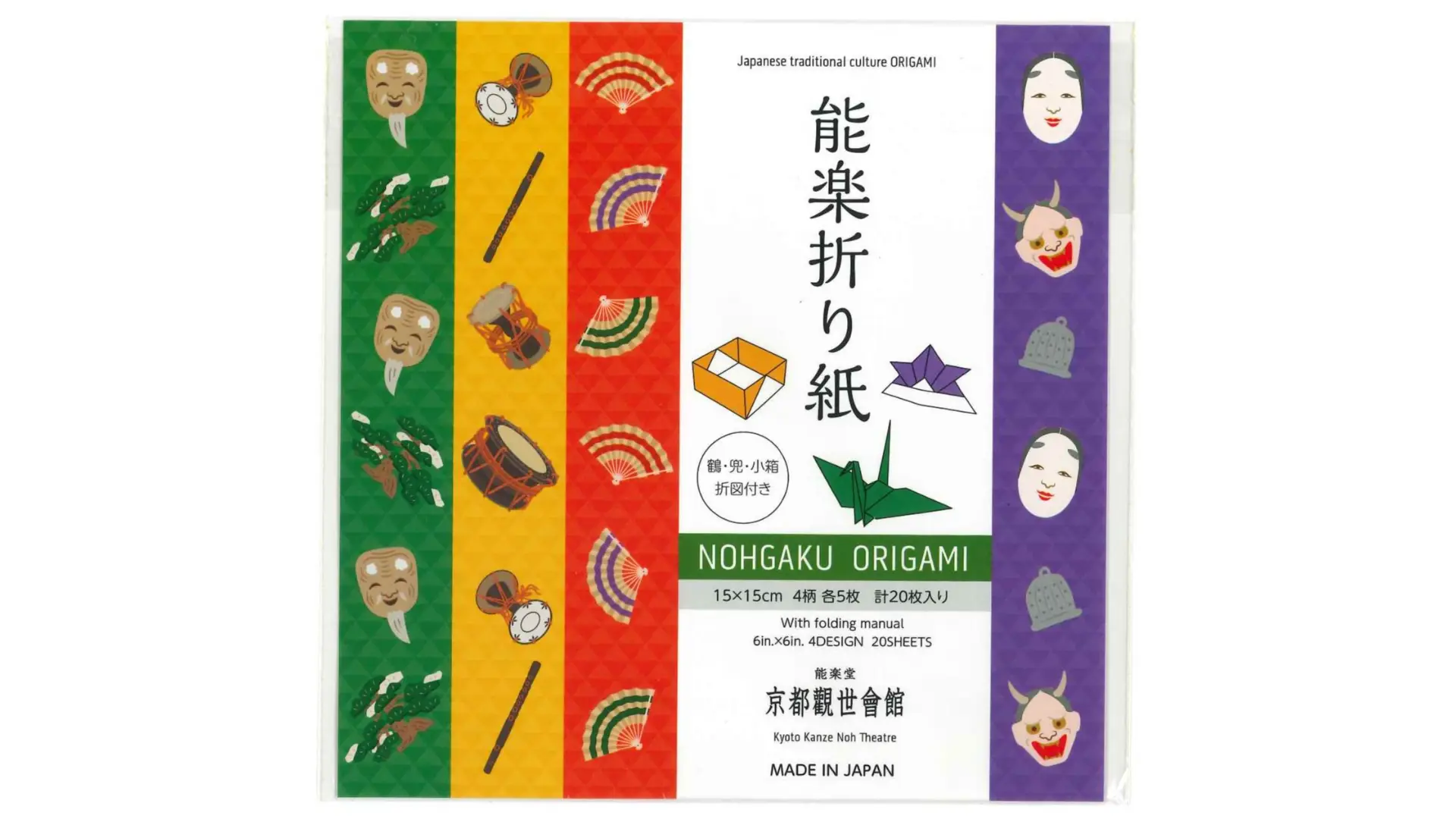

Souvenirs such as masking tape and origami goods also make great gifts for friends. The masking tape has lines in five colors inspired by the agemaku curtain, with designs of masks such as the hannya and ko-omote, giving it a cute, pop look. The "Noh Mask Origami" set includes folding diagrams for the Okina mask, a female mask, and the hannya mask so that you can fold your own noh masks.

There is also "Nohgaku Origami", which features patterns of masks and instruments used in noh.

By taking these souvenirs home, you can continue to feel close to noh even after you return to your own country, so be sure to choose something you like.

-

Masking tape

-

Noh Mask Origami

-

Nohgaku Origami

Services for International Visitors at Other Performances Too

ENTER NOH is not the only performance that international visitors can enjoy. Even if ENTER NOH is not being held at the time of your visit, Kyoto Kanze Noh Theater distributes flyers in English summarizing the plots of the plays being performed. At "Reikai", the regular performance series, you can also rent a subtitle device for 1,000 yen. Make use of these tools and discover the charms of noh.

Summary

Noh, one of the highest forms of traditional Japanese performing arts, has had a major influence on other Japanese cultural traditions such as kabuki and the tea ceremony. Even from a global perspective, it is one of the world's great forms of theater. Noh masks and costumes are highly artistic, and many noh stages are designated as national treasures or important cultural properties. Because noh expresses a solemn, spiritual worldview, it can be seen as a culture filled with the Japanese spirit and sense of beauty. Using this article as a guide, be sure to experience noh for yourself when you visit Japan.

Author

Freelance Announcer

Sayaka Motomura

Focused on sharing insights related to traditional culture, performing arts, and history.